The Beholder

Snapped’s Sanford S. Shaman in conversation with Lolo Veleko

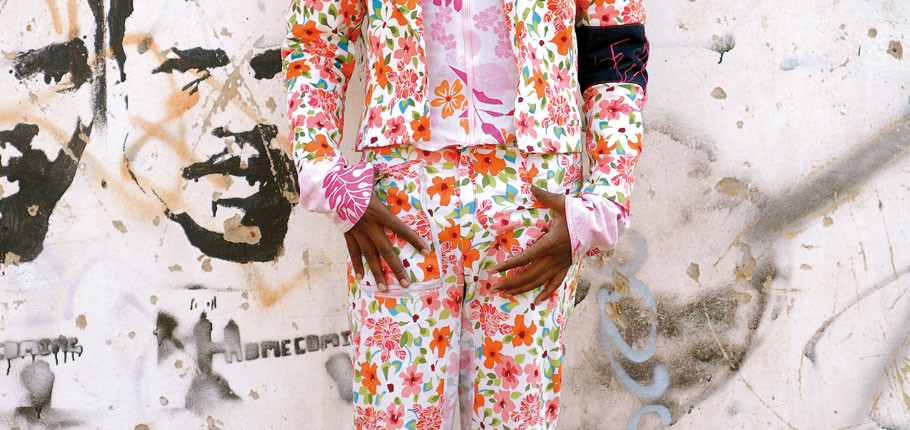

The wunderkind of South African photography, Lolo Veleko is garnering the type of international attention that is rare for a photographer from this country. In 2006 she was propelled into the international arena when Okwui Enwezor selected her for Snap Judgments, a comprehensive exhibition of contemporary African photography at New York’s International Centre for Photography. Singled out by the New York Times for her “her eye-tingling pictures of Johannesburg street fashion”, Veleko focuses upon the radical chic of black street-youth as a means to explore issues of race and identity. Fashion is her vocabulary – fashion on the edge – which becomes charged with a racial rhetoric vis-à-vis the “harassment” Veleko and those she photographs confront for their adherence to avant-garde couture. Repeatedly characterized as a continuation in the historic line of the Malian photographer Seydou Keïta (1921 – 2001), Veleko’s work is also frequently linked to that of the contemporary African photographer Samuel Fosso (born 1962 in Cameroon). But Veleko prefers to see her images more in the spirit of the Japanese Shoichi Aoki, who photographs Tokyo’s avant-garde street fashion for his publication, Fruits. Born in Bodibe, North West Province in 1977, Nontsikelelo (Lolo) Veleko grew up in Cape Town, and currently lives and works in Johannesburg. She studied graphic design at the Cape Technikon, and photography at the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg. In addition to exhibiting widely throughout South Africa, Veleko has shown her work in galleries and museums in Rome, the Canary Islands, Biel (Switzerland), London, and New York. Veleko shows regularly with the Linda Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg and Cape Town.

Sanford S. Shaman: Much of your recent work focuses on fashion. In light of the intensity of African photography today, how do you reconcile your exploration of fashion?

Lolo Veleko: Let me correct you and emphasize that my work centers around issues of identity through clothing.

SSS: Nevertheless, much has been said about what many writers describe as your interest in “fashion”, but no one seems to have explored your formal or informal connection to fashion photography particularly in light of your time in Cape Town where there’s growing international activity in that field.

LV: Perhaps this has been a fault on my side too, as I do not write much on my work, my influences, dreams, etc. But I grew up in Cape Town and my work thus far has always been working from my memories of Cape Town’s individuality. I must say, though, that when I left Cape Town I was studying graphic design and my sister was studying fashion, and secretly I admired what she did, but did not have the guts to pursue fashion as a subject. When I studied photography I looked up to Crispian Plunkett’s work as well as the work of Koto Bolofo and Gerda Genis.

SSS: You have said of your own work “it could be complicated, but I try not to let it go there!” Have you not perhaps carried that to an extreme with the emphasis on clothes and exterior appearances?

LV: To the best of my knowledge I have tried to simplify things but I think the more I consciously did that, the more it became complicated. My training is in basic journalistic photography, and I had to use that style yet deny much of what comes with it. I studied in a workshop [the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg] for really a short period of time, and all I have done thus far has been a sort of ambitious experimentation with colour film and printing. Anywhere else my work would not make it, as it is kind of risky work, not everyone’s cup of tea.

SSS: Your work in fact is in stark contrast to the contemporary African photography which is tough, harsh, and highly confrontational. I wonder if much of your success is not the result of offering a more palatable alternative.

LV: Perhaps! I really do not know as the response to the work varies in each country. My work is not specific; it flirts with fashion, politics, tradition, music, graffiti, etc. I think I offer photographs that speak of my time in relation to what is happening around me in an urban situation, because we as South Africans are dealing with issues of identity and finding ourselves through experimentation. This is not the experiment the colonialist had in mind – perhaps this is what makes a success of the work.

SSS: Clearly a key component of the work is the relationship between the photographer and the sitter. There are, however, differing interpretations of your approach to this. Writing about your Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder series, critic Rory Bester says that you make images “…in which the relationship between the photographer and the photographed isn’t quite clear”. Elsewhere your work has been described as suggesting an “implicit collaboration between sitter and photographer”. Just how are we to understand the dynamic that you cultivate between the photographer and the subject?

LV: Rory refers to the fact that I “dress up” myself and I imprint a bit of myself in the Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder series. [But] I would like to think that I had been through what they [the sitters] have been through. I had been harassed by people who felt I was not dressing-up like them and therefore [they assumed] I was thinking I’m better than they are. In Cape Town I had to stop wearing my short skirts [while] roller-skating and rollerblading in the streets. When I had a Mohawk, a lot of those people who claimed to be sure of who they were, suddenly isolated me from their circles. In short I can say I have been in the shoes of the misunderstood in my quest of discovering my many selves and this is what you actually find in all the photographs.

SSS: Obviously, you strongly identify with the sensibilities of your sitters.

LV: I mentioned once in an interview that at the time of taking the 2003-2005 images, it was not easy for the Johannesburg youth to hang around “Jozi” streets dressed up the way Thulani, Hloni and a few other [sitters] dressed. They faced harassment all the time, and most times I could hear people laugh at them, asking, “What the hell are they wearing?” But in 2006 the very same harassers are wearing those styles and have a “selective insomnia”. I still hear people at galleries too doing the same thing.

For me growing up in Cape Town, I had seen far more interesting young people dressed so sharp that it was almost like a celebration over there. As I got excited collaborating with them for the photographs, I yearned to show the work outside and blow it up big like billboards somehow, as a celebration of some kind of “gutsy” individuality at the time. But I feared for my subjects. I was scared the people photographed could face more harassment or even worse. I think … it was a better choice to show in a closed space than an open space especially here in South Africa.

SSS: But what about beyond South Africa? Your Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder series is generally recognized for its global appeal. It has even been described as an example of how “…globality has clearly replaced modernity as the currency of contemporary identity”.

LV: I suppose the statement is true and not true at the same time because nothing really has been replaced. Both modernity and globality are still currencies of contemporary identity. Look at David LaChapelle’s movie Rize and what’s happening in the ghettos in L.A. In Israel and Morocco the obvious American influences that are there are so amazing like hip-hop, sagging pants and “50 cent [hip-hop] chains” hanging on the youths’ necks – even the way they talk. [And] the streets of Tokyo early in 1992 till now in Harajuku have been a melting pot of Japanese youth defying traditional clothing and norms as we know them. They came up with a lot of crazy yet interesting experiments. For example, they cut up the kimono and wore it with a Chanel skirt with lots of accessories. Others were influenced by hip-hop, tanned their skin dark and some took punk and rock to another level. As South Africans we have not even discovered that part of things over there – or even here.

In France globalization as a topic, and making people ready for it, has been dealt with since the 80’s – whilst we were still struggling with the ills of Apartheid. So you can imagine how ready France must [have been] for it than we in South Africa. [But] South Africa can no longer see itself outside of a global movement even though sadly for us it’s happening at an extremely fast pace because it is still really new to us. [Isolated] geographically, and politically … far behind, … we have had to catch up. Sometimes that brings about qualities in photography and art, which I both hate and love.

But one thing I am sure of, is that the viewers from countries like Madagascar, Reunion Island and America can now identify with a Johannesburg youth [who is] visually unlike cliché images of Africa that are mass produced on a daily basis and forced down the throats of the public.

SSS: You’ve recently spent time in the UK. You were awarded a residency there with the International Photography Research Network (IPRN). How did you find the way of life there? Did it impact your work?

LV: My time in the UK was both eye opening and hard at the same time. I went from mid February until mid April 2007, and I was based at the University of Sunderland. The laws around street photography are harsh over there, and it was a definite requirement that I have public liability insurance as well as model release forms before I could even take my first photographs. The other difficulty was that I had to write letters for permission to [photograph] workers.

But also it is quite a tense environment over there, and Sunderland is a small city in the Northeast of England. It reminded me a lot of Johannesburg because of the fact that they once had a coal mine and a ship building industry that was really their source of income. And once both closed down, almost all the people over there were jobless, and they had to go for training in new technologies and mainly work in call centres. It brought about a body of work, that was shown in a group show in Finland, [and which was] not so different from what I deal with Identity.

SSS: This growing international acceptance of your work implies its universal appeal. But repeatedly you have explained your work as essentially grounded in racial issues from a highly personal perspective. In light of that, who is the audience that you are attempting to reach?

LV: With all my work I am trying to reach a universal audience. Although I use myself as an example, and use my life’s history of coming from a mixed heritage, I speak to all people. I decided to use clothing as a way of narrating this because all of us wear clothes/fashion. This might not be high fashion but we all dress up or down according to our influences, education, religion, etc.

SSS: But working through the gallery/museum/art publication world, are you also able to reach the street community that you photograph? Are you reaching – through the art world – the racially mixed people on whom you focus in notblackenough.lolo?

LV: With the notblackenough.lolo project, I am reaching the racially mixed people. This has been so evident in Barcelona where even there, there is prejudice amongst clans. The installation there caused so much debate that in a week there was no space to write in [the area designated for visitors’ comments], as people vented their feelings about this state of affairs. At the same time even though we speak highly of globalization, there is still a lot prejudice directed toward mixed race people, for example, read about what has been written on Obama who is running for president in the US. Read about the ethnic cleansing happening in North Africa in different states.

[But] I have not really reached a crowd of the street communities in this country for reasons I mentioned before (harassment of the people photographed). This is due to prejudice and fear to be “out of the box”! But time will tell because that is exactly what I dream of. It’s in the pipeline and it will be done soon when the time is right. I guess the challenge of photographing the “street” community is to then invite them and their friends and families to [the exhibition] space …[and] give them an idea where the images go, and what happens to them. So the duty for me does not end in just telling them where it is going to be shown, but to invite them there, to include them in academic discussions, and perhaps give them a chance to explain themselves – instead of me assuming things. Also to be there for them when they do not understand the art world as well as the history of the gallery and its importance in society – which I am also still discovering.

Okay! I’ll tell you my secret – the highest and the most important reason why I eventually opted for art galleries is because throughout history, art and art galleries seem to be highly protected. They seem to … have stood the test of time for generations. We are still learning about and experiencing art that was in existence before the time of Christ. I would like for my work to stand this test of time so that generations to come could be proud of us and would know where they are going from here. Besides I am coming from an historical background that only relied on the narration of stories, which I strongly value, but for me it was not enough. I believe by seeing. I visualize the narrations in the photographs. I even eat with my eyes first!

SSS: You certainly seem to be moving toward that place in history. I have repeatedly read that your work is a continuation in the historic line of Seydou Keïta. From a more contemporary point of view, critics also relate your work to that of Samuel Fosso.

LV: I can see why they view my work as a continuation from Seydou Keïta and Samuel Fosso, … because I specialize in portraiture and it is my love, as well as self-portraiture. And that is what Samuel has really been good at. Look, Africa in general is often shown in a harsh and difficult light and therefore the Malian photographers [like Seydou Keïta] decided to show the other side of this image of Africa – and that we all do! [But] I am one who is still finding out how theorists and critics operate, and most times find that its easy and lazy for them to just think of these two great photographers along with my work. My experimentation with film (colour film in which I was never trained nor printed), as well as the way I take the photographs (asking the subject for permission), and the location (the streets of Johannesburg particularly) has not been considered. Or if considered, it has been [de-emphasized] in the writings. Also the problem I think for them was that they would rather not liken my work to the Japanese photographer [Shoichi Aoki] who made the books Fruits, as academically it would undermine my work or something along those lines – [so] I have heard. But also I often wonder if there was no Seydou Keïta or Malick Sidibé – who they would liken my work to.

SSS: Your reference to Shoichi Aoki’s Fruits is very relevant and quite fascinating. Has this been an important influence for you? The Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder series in fact seems quite informed by Aoki’s Fruits.

LV: Concerning the Japanese influence – one day, one page, I saw one picture that stayed and tortured my mind since 1995. I tore the page kept it, protected it from water, fire and all the elements. I even traveled with it to Johannesburg. I do not know if this was Shoichi Aoki’s work but I loved the Japan I saw with that one image. It is of a “Lolita”¹ wearing a dark modern Victorian dress with a little handbag. [It evoked what] I had experienced in Cape Town [among] art students with no money for clothes in high school and at the Technikon, when they simply made their own. I could not afford a school bag. I sewed mine with a jean material I found at home and drew Garfield with funky colours outside as he was my favourite cartoon and my colleagues envied my bag.

So yes, in 2002 I starved in Switzerland for a week because I finally found a full-paged Fruits book by Shoichi and I bought it without twinkling an eye. My work has been influenced by many things… Identity was and is still high on my agenda.

¹ Sometime in the mid-nineties a fashion emerged among young Japanese women mimicking Victorian porcelain dolls “…wearing cute voluminous frilly and lacey knee length dresses, frill top socks and Mary Janes”. Referred to as “Gothic Lolita”, the look was taken up by Japanese pop stars and celebrities. According to the web-site Avant Gauche, “Gothic Lolita is still going strong in Japan, where every weekend in the Harajuku district of Tokyo sweetly dressed young women congregate to chat and giggle and have their pictures taken by beguiled tourists. Now mainly thanks to publications like [Shoichi Aoki’s] Fruits,

studied graphic design at the Cape Technikon, and photography at the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg. In addition to exhibiting widely throughout South Africa, Veleko has shown her work in galleries and museums in Rome, the Canary Islands, Biel (Switzerland), London, and New York. Veleko shows regularly with the Linda Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg and Cape Town.

Sanford S. Shaman: Much of your recent work focuses on fashion. In light of the intensity of African photography today, how do you reconcile your exploration of fashion?

Lolo Veleko: Let me correct you and emphasize that my work centers around issues of identity through clothing.

SSS: Nevertheless, much has been said about what many writers describe as your interest in “fashion”, but no one seems to have explored your formal or informal connection to fashion photography particularly in light of your time in Cape Town where there’s growing international activity in that field.

LV: Perhaps this has been a fault on my side too, as I do not write much on my work, my influences, dreams, etc. But I grew up in Cape Town and my work thus far has always been working from my memories of Cape Town’s individuality. I must say, though, that when I left Cape Town I was studying graphic design and my sister was studying fashion, and secretly I admired what she did, but did not have the guts to pursue fashion as a subject. When I studied photography I looked up to Crispian Plunkett’s work as well as the work of Koto Bolofo and Gerda Genis.

SSS: You have said of your own work “it could be complicated, but I try not to let it go there!” Have you not perhaps carried that to an extreme with the emphasis on clothes and exterior appearances?

LV: To the best of my knowledge I have tried to simplify things but I think the more I consciously did that, the more it became complicated. My training is in basic journalistic photography, and I had to use that style yet deny much of what comes with it. I studied in a workshop [the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg] for really a short period of time, and all I have done thus far has been a sort of ambitious experimentation with colour film and printing. Anywhere else my work would not make it, as it is kind of risky work, not everyone’s cup of tea.

SSS: Your work in fact is in stark contrast to the contemporary African photography which is tough, harsh, and highly confrontational. I wonder if much of your success is not the result of offering a more palatable alternative.

LV: Perhaps! I really do not know as the response to the work varies in each country. My work is not specific; it flirts with fashion, politics, tradition, music, graffiti, etc. I think I offer photographs that speak of my time in relation to what is happening around me in an urban situation, because we as South Africans are dealing with issues of identity and finding ourselves through experimentation. This is not the experiment the colonialist had in mind – perhaps this is what makes a success of the work.

SSS: Clearly a key component of the work is the relationship between the photographer and the sitter. There are, however, differing interpretations of your approach to this. Writing about your Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder series, critic Rory Bester says that you make images “…in which the relationship between the photographer and the photographed isn’t quite clear”. Elsewhere your work has been described as suggesting an “implicit collaboration between sitter and photographer”. Just how are we to understand the dynamic that you cultivate between the photographer and the subject?

LV: Rory refers to the fact that I “dress up” myself and I imprint a bit of myself in the Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder series. [But] I would like to think that I had been through what they [the sitters] have been through. I had been harassed by people who felt I was not dressing-up like them and therefore [they assumed] I was thinking I’m better than they are. In Cape Town I had to stop wearing my short skirts [while] roller-skating and rollerblading in the streets. When I had a Mohawk, a lot of those people who claimed to be sure of who they were, suddenly isolated me from their circles. In short I can say I have been in the shoes of the misunderstood in my quest of discovering my many selves and this is what you actually find in all the photographs.

SSS: Obviously, you strongly identify with the sensibilities of your sitters.

LV: I mentioned once in an interview that at the time of taking the 2003-2005 images, it was not easy for the Johannesburg youth to hang around “Jozi” streets dressed up the way Thulani, Hloni and a few other [sitters] dressed. They faced harassment all the time, and most times I could hear people laugh at them, asking, “What the hell are they wearing?” But in 2006 the very same harassers are wearing those styles and have a “selective insomnia”. I still hear people at galleries too doing the same thing.

For me growing up in Cape Town, I had seen far more interesting young people dressed so sharp that it was almost like a celebration over there. As I got excited collaborating with them for the photographs, I yearned to show the work outside and blow it up big like billboards somehow, as a celebration of some kind of “gutsy” individuality at the time. But I feared for my subjects. I was scared the people photographed could face more harassment or even worse. I think … it was a better choice to show in a closed space than an open space especially here in South Africa.

SSS: But what about beyond South Africa? Your Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder series is generally recognized for its global appeal. It has even been described as an example of how “…globality has clearly replaced modernity as the currency of contemporary identity”.

LV: I suppose the statement is true and not true at the same time because nothing really has been replaced. Both modernity and globality are still currencies of contemporary identity. Look at David LaChapelle’s movie Rize and what’s happening in the ghettos in L.A. In Israel and Morocco the obvious American influences that are there are so amazing like hip-hop, sagging pants and “50 cent [hip-hop] chains” hanging on the youths’ necks – even the way they talk. [And] the streets of Tokyo early in 1992 till now in Harajuku have been a melting pot of Japanese youth defying traditional clothing and norms as we know them. They came up with a lot of crazy yet interesting experiments. For example, they cut up the kimono and wore it with a Chanel skirt with lots of accessories. Others were influenced by hip-hop, tanned their skin dark and some took punk and rock to another level. As South Africans we have not even discovered that part of things over there – or even here.

In France globalization as a topic, and making people ready for it, has been dealt with since the 80’s – whilst we were still struggling with the ills of Apartheid. So you can imagine how ready France must [have been] for it than we in South Africa. [But] South Africa can no longer see itself outside of a global movement even though sadly for us it’s happening at an extremely fast pace because it is still really new to us. [Isolated] geographically, and politically … far behind, … we have had to catch up. Sometimes that brings about qualities in photography and art, which I both hate and love.

But one thing I am sure of, is that the viewers from countries like Madagascar, Reunion Island and America can now identify with a Johannesburg youth [who is] visually unlike cliché images of Africa that are mass produced on a daily basis and forced down the throats of the public.

SSS: You’ve recently spent time in the UK. You were awarded a residency there with the International Photography Research Network (IPRN). How did you find the way of life there? Did it impact your work?

LV: My time in the UK was both eye opening and hard at the same time. I went from mid February until mid April 2007, and I was based at the University of Sunderland. The laws around street photography are harsh over there, and it was a definite requirement that I have public liability insurance as well as model release forms before I could even take my first photographs. The other difficulty was that I had to write letters for permission to [photograph] workers.

But also it is quite a tense environment over there, and Sunderland is a small city in the Northeast of England. It reminded me a lot of Johannesburg because of the fact that they once had a coal mine and a ship building industry that was really their source of income. And once both closed down, almost all the people over there were jobless, and they had to go for training in new technologies and mainly work in call centres. It brought about a body of work, that was shown in a group show in Finland, [and which was] not so different from what I deal with Identity.

SSS: This growing international acceptance of your work implies its universal appeal. But repeatedly you have explained your work as essentially grounded in racial issues from a highly personal perspective. In light of that, who is the audience that you are attempting to reach?

LV: With all my work I am trying to reach a universal audience. Although I use myself as an example, and use my life’s history of coming from a mixed heritage, I speak to all people. I decided to use clothing as a way of narrating this because all of us wear clothes/fashion. This might not be high fashion but we all dress up or down according to our influences, education, religion, etc.

SSS: But working through the gallery/museum/art publication world, are you also able to reach the street community that you photograph? Are you reaching – through the art world – the racially mixed people on whom you focus in notblackenough.lolo?

LV: With the notblackenough.lolo project, I am reaching the racially mixed people. This has been so evident in Barcelona where even there, there is prejudice amongst clans. The installation there caused so much debate that in a week there was no space to write in [the area designated for visitors’ comments], as people vented their feelings about this state of affairs. At the same time even though we speak highly of globalization, there is still a lot prejudice directed toward mixed race people, for example, read about what has been written on Obama who is running for president in the US. Read about the ethnic cleansing happening in North Africa in different states.

[But] I have not really reached a crowd of the street communities in this country for reasons I mentioned before (harassment of the people photographed). This is due to prejudice and fear to be “out of the box”! But time will tell because that is exactly what I dream of. It’s in the pipeline and it will be done soon when the time is right. I guess the challenge of photographing the “street” community is to then invite them and their friends and families to [the exhibition] space …[and] give them an idea where the images go, and what happens to them. So the duty for me does not end in just telling them where it is going to be shown, but to invite them there, to include them in academic discussions, and perhaps give them a chance to explain themselves – instead of me assuming things. Also to be there for them when they do not understand the art world as well as the history of the gallery and its importance in society – which I am also still discovering.

Okay! I’ll tell you my secret – the highest and the most important reason why I eventually opted for art galleries is because throughout history, art and art galleries seem to be highly protected. They seem to … have stood the test of time for generations. We are still learning about and experiencing art that was in existence before the time of Christ. I would like for my work to stand this test of time so that generations to come could be proud of us and would know where they are going from here. Besides I am coming from an historical background that only relied on the narration of stories, which I strongly value, but for me it was not enough. I believe by seeing. I visualize the narrations in the photographs. I even eat with my eyes first!

SSS: You certainly seem to be moving toward that place in history. I have repeatedly read that your work is a continuation in the historic line of Seydou Keïta. From a more contemporary point of view, critics also relate your work to that of Samuel Fosso.

LV: I can see why they view my work as a continuation from Seydou Keïta and Samuel Fosso, … because I specialize in portraiture and it is my love, as well as self-portraiture. And that is what Samuel has really been good at. Look, Africa in general is often shown in a harsh and difficult light and therefore the Malian photographers [like Seydou Keïta] decided to show the other side of this image of Africa – and that we all do! [But] I am one who is still finding out how theorists and critics operate, and most times find that its easy and lazy for them to just think of these two great photographers along with my work. My experimentation with film (colour film in which I was never trained nor printed), as well as the way I take the photographs (asking the subject for permission), and the location (the streets of Johannesburg particularly) has not been considered. Or if considered, it has been [de-emphasized] in the writings. Also the problem I think for them was that they would rather not liken my work to the Japanese photographer [Shoichi Aoki] who made the books Fruits, as academically it would undermine my work or something along those lines – [so] I have heard. But also I often wonder if there was no Seydou Keïta or Malick Sidibé – who they would liken my work to.

SSS: Your reference to Shoichi Aoki’s Fruits is very relevant and quite fascinating. Has this been an important influence for you? The Beauty in the Eye of the Beholder series in fact seems quite informed by Aoki’s Fruits.

LV: Concerning the Japanese influence – one day, one page, I saw one picture that stayed and tortured my mind since 1995. I tore the page kept it, protected it from water, fire and all the elements. I even traveled with it to Johannesburg. I do not know if this was Shoichi Aoki’s work but I loved the Japan I saw with that one image. It is of a “Lolita”¹ wearing a dark modern Victorian dress with a little handbag. [It evoked what] I had experienced in Cape Town [among] art students with no money for clothes in high school and at the Technikon, when they simply made their own. I could not afford a school bag. I sewed mine with a jean material I found at home and drew Garfield with funky colours outside as he was my favourite cartoon and my colleagues envied my bag.

So yes, in 2002 I starved in Switzerland for a week because I finally found a full-paged Fruits book by Shoichi and I bought it without twinkling an eye. My work has been influenced by many things… Identity was and is still high on my agenda.

¹ Sometime in the mid-nineties a fashion emerged among young Japanese women mimicking Victorian porcelain dolls “…wearing cute voluminous frilly and lacey knee length dresses, frill top socks and Mary Janes”. Referred to as “Gothic Lolita”, the look was taken up by Japanese pop stars and celebrities. According to the web-site Avant Gauche, “Gothic Lolita is still going strong in Japan, where every weekend in the Harajuku district of Tokyo sweetly dressed young women congregate to chat and giggle and have their pictures taken by beguiled tourists. Now mainly thanks to publications like [Shoichi Aoki’s] Fruits, Gothic Lolita has come to the attention of the world Outside Japan. See: avantgauche.co.uk.